The Ontario Turtle Conservation Centre is a registered charity operating a hospital for Ontario’s native turtle species. This hospital is one of the few wildlife hospitals Accredited by the College of Veterinarians of Ontario (CVO). This accreditation process ensures that the hospital meets the strict standards of the CVO. Accreditation requires that a licenced veterinarian runs the hospital, and that it is operated with the same standards as a veterinary hospital that admits owned animals. Seven of the eight species of Ontario’s turtles are now listed as species at risk provincially, and eight of eight federally. Injuries to turtles from automobiles, boats, fish hooks, dogs, and humans, are second only to habitat destruction, as a cause for many of the species’ decline.

While other species of wildlife are also injured and killed on our roads, most animals have young from the previous year ready to mate and replenish the population. Unfortunately, this is not the case for turtles. Less than 1% of turtle eggs and hatchlings will survive to adulthood. This, combined with the fact that turtles can take anywhere from 8 to 25 years to reach maturity, means that populations cannot tolerate any additional losses. Every turtle saved is beneficial to the population. In fact, one study showed that for snapping turtles, it will take about 59 years to be able to replace themselves in the population. It takes THAT long, to ensure that just one will grow up to be able to replace these long-lived species. How long do they live? Nobody knows exactly, but it is not unreasonable for a snapping turtle to live 100 years or even more, and we are getting more and more information about other species, that show that they too have very, very long lives.

This long life means that each adult is extremely difficult, or impossible to replace in the population. Unlike most other species, turtles cannot make up for any additional losses, and the population cannot recover from the extra deaths such as those from roads. The number of turtles that we save, has a population impact and helps to buy time to fix the problem. Prevention of road mortalities will come by providing safe road access in the way of ecopassages. More and more of these are being implemented every year, with successful reduction in the number of road mortalities.

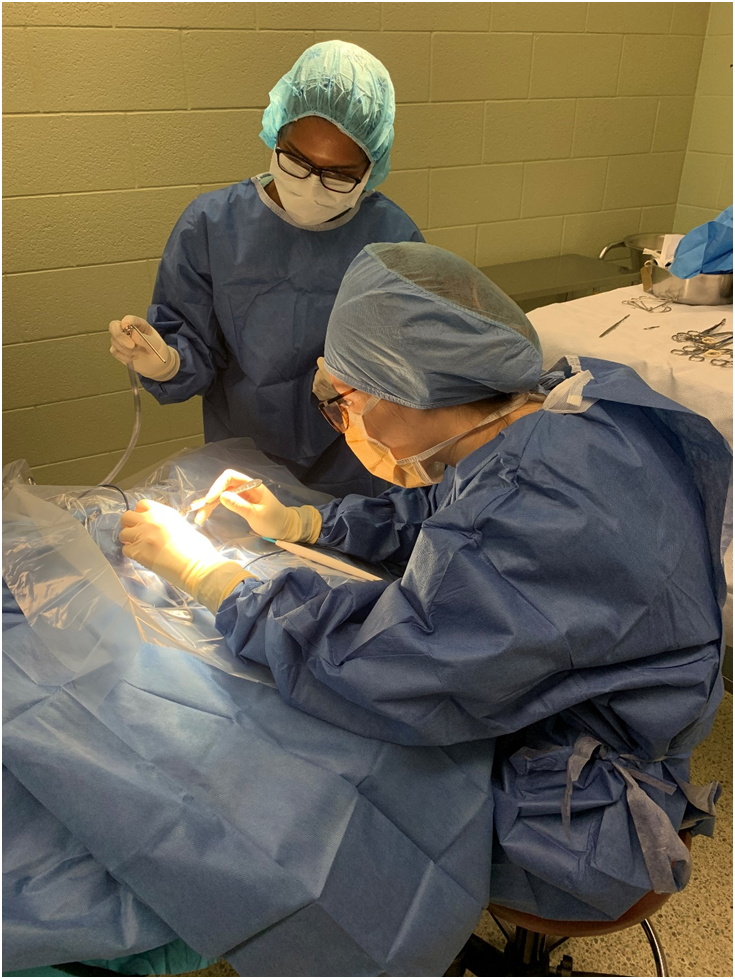

Vet Tech Amanda Klack (left) assisting Dr. Sue Carstairs

OTCC is the only wildlife rehabilitation centre dedicated solely to providing medical and rehabilitative care to Ontario turtles. Once healed these turtles are released back into their natural habitat where they can continue to reproduce for many decades.

In 2009, we admitted a total of 50-80 turtles per year. This number has climbed steadily as people across the province learn about the work we do and the importance of turtles to their ecosystems. The admission numbers have steadily climbed, and 2017 saw 920 admitted turtles, in 2018 the number was 938, and in 2019 we saw a record number of 1498 admissions. In 2020, despite pandemic restrictions, a cool spring, and an excessively hot summer, admissions were still over 1,000 cases. In 2023, OTCC admitted a record 1,900 turtles, incubated 7,100 eggs, and released 3,400 turtles back to their home wetlands.

The centre operates under the leadership of Executive Director Dr. Sue Carstairs, Medical Director for the Turtle Hospital. OTCC is supported by a province-wide network of veterinarians, private clinics, and other wildlife centres who help to get the turtles immediate care while transport is being arranged to OTCC. These veterinarians receive any needed training, and ongoing support from Dr. Carstairs, and they act as First Responders if finders are unable to transport the turtles directly to us. Visit the Turtle Drop-off page for more information about what to do if you find an injured turtle.

Most of the turtles are brought to our hospital with thanks to Good Samaritans from across the province, with help from our Turtle Taxi Volunteers, that number over 800! These turtles come from across their home range in Ontario. Southern Ontario is THE place for turtles in Canada, with a higher concentration and number of species than anywhere else in Canada.

Educating the public about what to do if they see a turtle on the road, or find an injured turtle, has lead to our admission number increasing greatly. This means that more turtles are getting the help they need to get back home. We have a network of “First Responders” across the province, which are mainly veterinarians who donate their time to help turtles in their area, until they can get transported to OTCC for surgery and continued care. This way, turtles get quick access to emergency care. These First Responders are provided with the materials and training they need, to provide this care. We can’t thank them enough for providing this vital role.

Why Do Turtles End Up In Hospital?

The majority of cases brought to the hospital are turtles that have been injured on our roads. You can’t go more than 1.5 km in southern Ontario without running into a road. Since our turtles often cover many kilometers in search of mates, feeding grounds, preferred summer hang-outs, and nesting sites, they invariably encounter roads in their travels. Both male and female turtles are actively crossing land, during the spring months. In fact, we see about 50% males and 50% females. Males tend to move earlier than females, and we see them out early spring and throughout the summer. Females tend to have a large peak in admissions during the peak nesting time in June.

The figure above shows our admissions for 2017, from across the turtles’ home range in Ontario.

Road Density map for southern Ontario. Unfortunately, the highest density for roads is also the highest density for turtles!

The injuries we see vary greatly but are generally very rewarding to treat since turtles have incredible resilience and their healing ability is probably better than any other species. It takes a dedicated team of professionals in the hospital, and a lot of time, but the results can be astounding.

As an example, here is a case of a snapping turtle that was hit by a car on June 1, 2017. Head injuries are very common in snapping turtles since they cannot protect their head in their shells as other turtle species can. When he first came in, the severity of his injuries was clear. He was given strong pain medication and fluids, and his general condition was stabilized before surgery was attempted. He was then anesthetized so that he could be put back together. He was very quiet for a long time and had to be kept in very shallow water to prevent drowning. Fast forward to August 15, and he is now very difficult to keep confined, and is slated for release this week!

Below shows his progress; from left to right- first admission, under anesthesia, and climbing out of his container keen to go home! He is very alert, has normal eyesight, and is very nimble. A true success story!

Another common reason for admission to our hospital is ingestion of fishing hooks. It is now illegal in Ontario to fish for any species of turtle, but turtles do still sometimes accidentally ingest hooks. These can cause significant problems as you can imagine! Removal is seldom easy, and requires anesthesia and often the use of an endoscope to retrieve them. With thanks to funding from the Gordon and Patricia Gray Animal Welfare Foundation, we were able to purchase an endoscope that allows retrieval of these hooks from the stomach. Notice in the X-ray (below), that this painted turtle also has had surgery to repair a shell fracture (see the wires in his hind end). The fish hook was found while we were doing routine X-rays and wasn’t even the reason for admission!

Above Left to Right

Using our endoscope to remove a fishing hook/Suturing a wound/Examining a blood film from a turtle.

Some amazing ‘Before’ (LEFT) & ‘After’ (RIGHT) shots to show how amazing turtles are at healing!

Emergency Medical Care

OTCC is well known throughout Ontario and receives injured turtles from every corner of the province. Because prompt medial care can be the difference between life and death, OTCC holds Turtle Trauma Workshops to help train veterinarians and rehabilitators from a variety of organizations across Ontario. Once stabilized, the turtles are transferred to the OTCC facility for ongoing care until they are ready to be released back into the wild. Our network of over 100 Turtle Taxi volunteers is instrumental in the transport of injured turtles from all parts of Ontario, often taking part in a ‘turtle relay’ to cover long distances and get our patients admitted to OTCC quickly for ongoing care.

Injuries &Treatment

The turtle’s shell is made of bone, covered by a modified ‘skin’. When a turtle’s shell is fractured, putting it back together is therefore actually orthopedic surgery! We repair fractures with a variety of different methods depending on the species and type of fracture.

We stabilize the fracture sites initially using an adhesive and tape. The pieces are then often wired, using orthopedic wire and holes drilled with a dental drill, under anesthetic.

One thing we no longer recommend for traumatic fractures, is the use of epoxy patches.These tended to hide underlying infection, and make it impossible to see or treat this. This often would lead to a fatal infection developing.

Although the fracture of the shell is the most obvious injury, it is often the internal damage that is more life threatening. Just like any animal that has undergone extensive trauma, the turtle undergoes shock in the same way. This is why access to timely veterinary care is so important to have the greatest chance of saving them.

Facial injuries are also common. Fractured jaws are wired in a similar manner to mammals, using orthopedic wire to reunite the pieces. Of course, anesthetic is always needed for this. Other surgeries frequently performed, include surgery to remove fishing hooks. These can become lodged in the head, mouth, stomach or intestines, and can easily become fatal. Turtles are also brought in for non-traumatic injuries, including abscesses of the ‘ears’, generalized infections, and pneumonia.

Recovery & Release

Turtles are released back into the wild once healed

Turtles are held at the OTCC until they are fully healed. Some turtles admitted early in the season can be released later in the same season. However, many require an overwinter stay. All the fixation devices are removed prior to release, and it is important to release the turtles very close to where they were rescued from. We usually look for the nearest body of water, within 1km of their rescue site. This is best for the turtles, and this is also the law.

The Role of Outreach

OTCC runs an extensive outreach and education program with goals of decreasing the number of turtles injured injured, decreasing rates of poaching for food or the pet trade, and increasing habitat saved for future generations of turtles. Visit the outreach and education program page to learn more.

Rehabilitation Standards

Th OTCC adheres to the laws and practices laid out by government of Ontario. Our authorization is issued to us by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) and covers reptiles only. This means that we can rehabilitate native reptiles but not other native animals. We focus on turtles only. We cannot treat pet turtles.

For more information on wildlife rehabilitation in Ontario please read:

- What to do if you find a sick, injured or orphaned wild animal

- Ontario Wildlife Rehabiltiation and Education Network (OWREN website)

The Minimum Standards for Wildlife Rehabilitation, 3rd Edition

We follow the rehabilitation standards developed by the National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association (NWRA). The Minimum Standards for Wildlife Rehabilitation, 3rd Edition, is based on accepted norms in biology, medicine, behavior, natural history, and, of course, wildlife rehabilitation. The information in this publication pertains to all who rehabilitate wildlife, regardless of numbers and types of wildlife cared for, budget size, number of paid or volunteer staff, and size and location of activity.

Some Very Interesting Cases

While the majority of our hospital admissions are victims of road injuries, we do also see a significant number of turtles brought in for other reasons. Fishing by-catch is quite common, and sometimes we even find the fish hooks incidentally, while their initial xrays are carried out. Some turtles brought in have old wounds from previous trauma, along with new ones.

We also see a significant number of predation attempts – both by domestic dogs and natural predators. This predation seems to be increased during times of extreme heat and drought, and may suggest that global warming is having an impact on this additional threat.

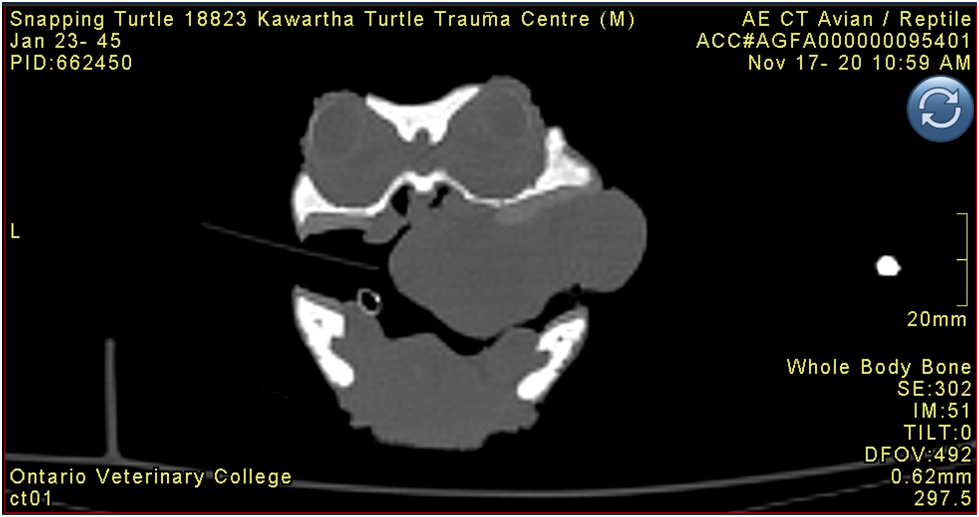

Snapping Turtle 18-823

One notable case is a very large snapping turtle that was brought in by a member of the public because they had seen a large lump protruding from his mouth. First of all, what a wonderful person to care enough to alert us to this turtle. And second of all, this person took it a step further and actually caught this turtle and brought him to us! (please be careful when handling wild snapping turtles, and see our section on handling for best practices!) To see tumours of any kind in turtles is very unusual, so we were curious as to the cause. We removed the mass, but were surprised to find the pathologist report did not find any malignancy. However, the mass grew back so we decided to investigate even further. We took him to the Ontario Veterinary College, where Dr. Chris Dutton and team (Dr. Dutton also is a member of the OTCC team!) used a CT scan to really ‘look’ at the mass, and used this to guide another full removal. This deeper removal showed a tumour, but locally invasive only. There is a chance that removal of this lump won’t cure him, but we have given him the best chance possible, and we hope that this will allow release of this wonderfully magnificent turtle!

Cataract

Another very interesting case came in the form of a snapping turtle who was an annual resident in the area of the Toronto Yacht club. He was seen there every year, but that particular year, they noticed he didn’t seem to be doing well. We discovered that this old guy had only one eye, and the remaining eye was blind due to a cataract. We decided to see if we could find a veterinary ophthalmic surgeon who would be willing to help with this case. If we could return the sight in his remaining eye, there was a good chance he could be released again.

Luckily, Dr. Joe Wolfer of The Toronto Eye Clinic, very kindly offered his expertise. The Toronto Wildlife Centre generously was helping OTCC house turtles at this time, so we all took part in this case!

While a cataract removal in a snapping turtle had never been documented before, Dr. Wolfer was keen to try. He was successful in removing the cataract, giving the turtle sight once more! After we were sure he was eating and able to find his food, he was released back to the Toronto Harbour. See the photos below, to see how this surgery was carried out!

The hospital as a monitor of the health of turtle populations

OTCC’s hospital not only admits and treats individuals from across the province, but it also serves as a monitor of the health of turtle populations in general, as well as the health of the whole ecosystem that the turtles live in. Any turtles admitted with signs of illness can be tested as to cause. For example, we recently completed a study of painted turtles admitted to the hospital from 2011-2020, with signs of abscesses of the inner ear. One theory as to the cause of these abscesses, is environmental contamination in the form of PCBs. This was the first study of this kind to be carried out in Canada, and has been submitted for publication.

We also recently completed a study of Ranavirus in turtles of Ontario. This virus affects cold-blooded animals such as turtles, amphibians and fishes, and has caused major issues with populations world-wide, and mass mortality in some cases. It had not been studied in turtles in Canada previous to our study. We sampled a large group of turtles that were showing no symptoms, and found that quite a lot of them were actually carrying this virus. The results were published in the journal Virology in partnership with Christopher J. Kyle, Sibelle Torres Vilaça, of Trent University. The results of this study revolutionized our understanding of this virus. We are now working on discovering if asymptomatic positive cases resolve on their own, or whether they progress to signs of disease.

Our unique access to these individuals, allows a random sample to be taken from across the province, and allows us to track potential health threats to these turtles. With the many threats already experienced by our turtle populations, health issues could pose an additional very dangerous concern.

Above – the location of positive cases of Ranavirus found, in samples taken at OTCC.

Above – the location of cases of Ranavirus, as compared to the level of Ranavirus found in the water. Red indicates the highest amount of virus in the water, and blue indicates the lowest.